Theoretical Perspectives on Scripture as Communication

Pages 1-138

Terminology and Context for Hermeneutics

Pages 19-28

- Concepts are not what we think about; they are what we think with. - Kathleen Callow (19)

- Hermeneutics is the study of the activity of interpretation.

- All reading is interpretation.

- Meaning is what we are trying to grasp when we interpret.

- meaning is the communicative intention of the author, which has been inscribed in the text and addressed to the intended audience for purposes of engagement. (22)

- Authorial intention is not their motive but what they actually communicate by intention in a text. The latter is accessible to the reader while the former is not.

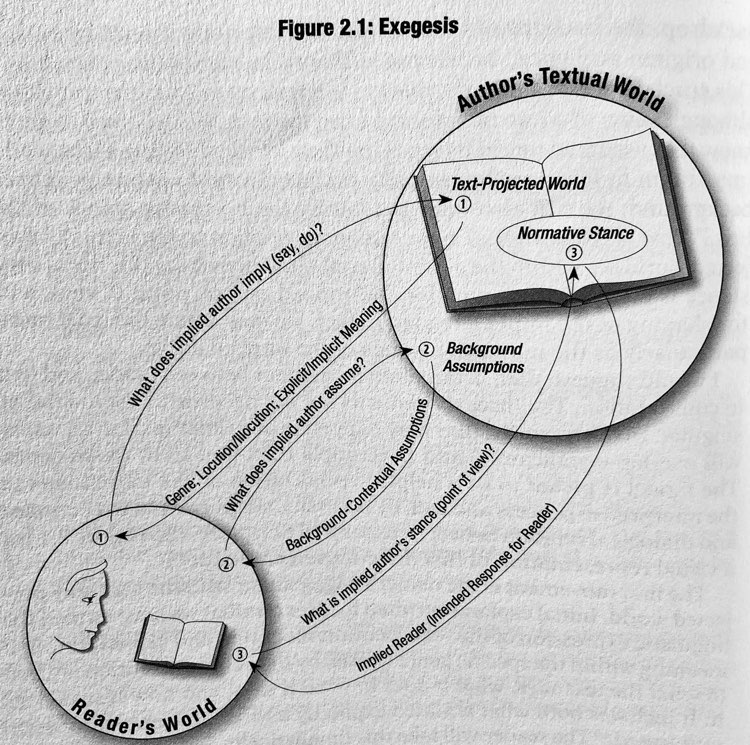

- Exegesis is the task of carefully studying the Bible in order to determine as well as possible the author’s meaning in the original context of writing. (23)

A Communication Model of Hermeneutics

Pages 29-56

- None of us is a clean slate. We have been guided, often without much conscious awareness, toward a theoretical understanding of what the Bible is and how it should be approached. (30)

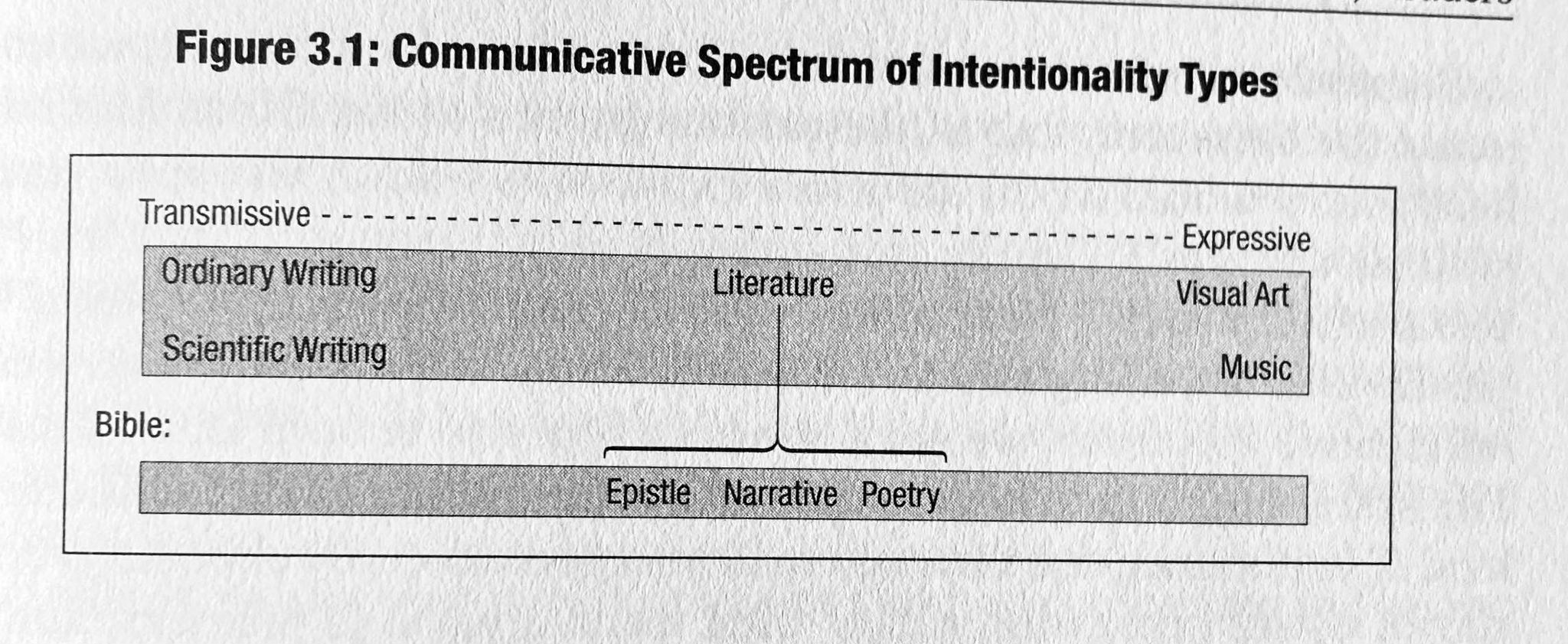

- Two theories to help understand Scripture as communication is speech-act theory and relevance theory.

- Speech-act theory insists that verbal utterances not only say things but also do things.

- Locution is what is said; illocution is what we verbally accomplish in what we say; perlocution is what the hearer does in response to that utterance.

- Relevance theory claims an utterance requires hearers to infer more than is provided in the utterance itself and that they will have to discern what is most relevant to understanding the utterance.

- “My stomach is growling” communicates both the explicit information about my stomach’s activity and implicit information that I am hungry.

- Assumed context refers to the relevant presuppositions shared by speaker and hearer that make communication work.

- The implied reader is the reader presupposed by the narrative.

Authors, Texts, Readers: Historical Movements and Reactions

Pages 57-78

- Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834) is the “father of modern hermeneutics” who proposed that we can come to further understanding by connecting to the author.

- Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911) furthered Schleiermacher’s ideas by insisting we should try to understand the author better than they understood themselves.

- “New Criticism” starkly opposed the need to connect to the author’s world to attain meaning. They shifted to the text as the sole vehicle of meaning—insisting the text is autonomous.

- Repeated interaction with a text—particularly with the awareness of one’s own presuppositions, the otherness of the text, and the storied nature of the whole—can move one productively toward textual understanding. (74)

- 🔥At its heart, the hermeneutical process is open-ended, never fully completed. Maybe this should not surprise us, since an interpersonal view of hermeneutics invites the analogy of relationship or friendship, whose goal is not completion for its own sake but continual longing to know and be known. (74)

Some Affirmations about Meaning from a Communication Model

Pages 79-99

- The basis of the Great Commission is rooted in the authority of Jesus through his presence with his followers, a major stress in Matthew since it begins and ends with this theme (1:23; 28:20). (86)

- Where the author places certain verses affects its meaning. The culmination of Matthew is 28:17-20 where the readers hear how the now eleven disciples still struggled to trust Jesus and grasp who he truly is. Matthew describes the disciples with “little faith” five times. (86)

- Determinacy means that interpretations can be weighed on the basis of their alignment and coherence with an author’s communicative intention. It means that, in interpretative theory, we can describe and explore the limits of meaning (we can affirm its bounded nature). (87)

- Each time we return to the text we are different: we ask different questions, we bring different issues, we arrive at different insights. Our contextualizing of the text occurs between the textual world and our world, and this interaction helps to explain our experience of flux in relation to meaning. (88)

- Although we cannot access meaning perfectly, we should still try to reach for it. Some may argue that truth is relative since no human can know truth in any objective fashion. Others who claim the existence of objective truth also posit the existence of objective knowledge—meaning we can view truth from an objective vantage point. To avoid extremes, we clearly distinguish between objective truth or reality and the always-subjective human appropriation of truth (89).

- John may be using ambiguous wordplay in John 1:5 when he says the darkness has not katalambanó it. It can be translated as either “understood” or “overcome.” In 12:35, darkness overcomes the light but misunderstanding is a Johannine motif (8:27). (92)

- In John 3, he plays on the word anóthen which can mean either “from above” or “again.” Jesus says a person must be born from above (3:3; confirmed at 3:12-13), while Nicodemus misunderstands and gets preoccupied by the literal notion of being born again (3:4). (93)

- There is a probably wordplay on zōn when Jesus offers “living water” but the Samaritan woman may have misheard as “running water.” (93)

- We need to be aware of our cultural gaps from the Bible when we approach the text. Most ascribe Jonah’s running away from God’s call to cowardice. However this does not come from the text—only the fear of God is mentioned in 1:9. His real reason is made apparent when understanding the social world of his day. Jonah, an Israelite, flees God’s command to preach at the capital city of Israel’s archenemy out of hatred of his enemies as well as knowing God would show mercy if they repented. (93-94)

- Most of us in the West tend to individualistically read 1 Corinthians 3:16 hearing the singular “you” when Paul says “Do you not know that you are a temple of God and that the Spirit of God dwells in you?” (NASB). What’s surprising is that Paul is referring to the corporate church as God’s temple and dwelling place for God’s Spirit—clearly indicated from his usage of the second-person plural form (“you”) in the Greek. (94)

- In my reading, Paul’s central concern in 1 Corinthians 8 is the Corinthian’s participation in idolatry as they join in temple feasts. 🔥The root problem is idolatry, specifically, attempting to affirm one’s allegiance to the one true God, while playing at the edges of idolatrous practice, when the call of God is to exclusive allegiance. This normative stance seems quite transferable to my cultural context, since today’s contemporary church struggles with compromised allegiance, as did the Corinthian church, although not in relation to temple feasts. For instance, the siren song of materialism woos us from wholehearted allegiance to God toward placing possessions, money, and comfort at the center of our existence. The normative song of resistance to idolatrous temptations resonates well in this different key. (96)

Developing Textual Meaning: Implications, Effects, and Other Ways of Going “Beyond”

Pages 100-119

- Particularly helpful is the observation that, by citing a brief part of another text or even alluding to it, an author may be evoking the entire context, message, or story of that other text. One example is the recognition that an important way the Gospel writers communicate the fulfillment of Israel’s promised restoration in Jesus is by evoking Isaiah’s “new exodus” motif (e.g. Matt. 1-2; Mark 1:1-3)… this way of evoking whole stories and ideas by means of allusion makes much sense of how we understand New Testament writers using Old Testament texts. (110)

- Terms

- Locution - a saying/utterance

- Illocution - what the saying does

- Perlocution - response of a hearer

- EXAMPLE:

- I call out to Libby, “Watch out for the geese!” (locution)

- The illocutionary act is an act of warning and want to elicit a certain response from Libby (perlocution).

- If Libby understands my warning, my illocution is successful.

- If Libby move away from the geese, my perlocutionary intention will have been successful.

- In the end, how are these distinctions important for interpreting the Bible? They are important because, as is so often the case, the writers of Scripture have perlocutionary intentions for their audience beyond understanding what is communicated. Biblical authors certainly want to be understood when they warn and exhort and plead and praise. Yet they also have intentions for their audience that go beyond simply understanding what they are saying and doing with their words. The authors have as extensions of their communicative intentions the shaping of their audience to respond in certain ways. They warn so that their audience will be deterred from harm; they exhort so that their audience will follow the paths they set forth; they praise God—and implicitly invite their audience into of God with them. (114)

- sensus plenior - the “fuller sense” of the text in later contexts.

- “applicational elephants… from interpretive threads.”

An Invitation to Active Engagement: The Reader and the Bible

Pages 120-138

- What we see when we think we are looking into the depths of Scripture may sometimes be only the reflection of our own silly faces. - C.S. Lewis (120)

- Presupposition - any preconception that is part of our thinking as we come to interpret the Bible.

- “[Presuppositions] can enable creative and penetrating insight… [yet] the same commitments may also lead to eisegesis, selective blindness, and dubious ranking of [textual] elements as central or peripheral.” (123)

- Tuner, “Theological Hermeneutics,” 57-58. As you may hear, the word “eisegesis” is related to “exegesis.” While exegesis is a “drawing out” of the author’s meaning, eisegesis refers to imparting one’s own meaning into the text.

- Presuppositions “gone bad” are what Osborne refers to as prejudices. A prejudice is the denigration of a presupposition into an “a priori grid” that then predetermines what the text can or cannot mean. A prejudice, by definition, does not budge even when presented with powerful textual evidence to the contrary. Instead, a prejudice forces the text into alignment with its own position. (123)

- 🔥Trying to discover our presuppositions can be rather like trying to see our own blind spots—very difficult without outside assistance. The Spirit’s work in our lives, the influence of the larger Christian community, and the Scriptures themselves when read with a submissive spirit are central correctives to our potential prejudices. (123)

- The reader’s misreading is not a part of the text’s meaning. (124)

- Reading the Bible is a cross-cultural experience and inextricably has an “otherness” to it.

- 🔥If we are routinely experiencing the Bible as “nonthreatening platitudes” rather than a wake-up call to new ways of thinking, being, and doing, we are probably not reading well. (125)

- The Bible is meta-cognitive in scope. So our reading of it should allow for the entire range of responses it envisions for readers, cognitive and otherwise. To read only for the cognitive knowledge we can get from the Bible diminishes its value and purposes. Part of allowing Scripture to shape us is submitting to it not only with our minds but also with our affections and our actions. Only in this way will we truly and personally know. (128)

- There is no one-to-one correspondence between personal piety and correct interpretation, although this conviction is sometimes used as a trump card for interpretive correctness (“I prayed and God told me that this passage means…”). (128)

- We should seek to become the “implied reader”, someone who embodies every right response to the author’s communicative intention.

- Implied reader for Habakkuk:

- One who waits on God when God’s justice seems to be absent. (1:2-4)

- They have a trusting reception of what God has to say. (2:1)

- The faithful, trusting stance of the righteous person is the model for the implied reader. (2:4)

- Called to fully embrace the final stance of joy and faith amidst barrenness and ambiguity. (3:16-19)

- Texts were read aloud in the ancient world since literacy was scarce.

- Some good guidelines for reading:

- Biblical genres

- Language

- Social setting

- Literary context

- We listen well by reading the Bible on its own terms, not assuming that we have always understood its message, not imposing our own messages on it. Instead, we take care to hear a biblical text in its own setting, so we might in the end hear it in ours. (136)